A USAMTS Year 34 Round 1 Review

What’s USAMTS?

USAMTS is a free, high school oriented, proof based contest that is funded by NSA. The contest consists of three rounds, each with 5 problems and worth 5 points. The contest is fully remote and is a month long since the problems are hard enough to not get immediately. The contest is a great way to think about problems constantly and sharpen your math skills.

Problem 1

Alright. Not too much to say on this problem, except I probably could’ve been better in the way that I approached it. I just did trial and error with minor casework that eventually got the answer.

Except, with that circle with diameter of 5 that is given to you, you can immediately notice that there are three one diameter circles that go inside of it.

That can give a head start, and then what I did from there was basically do possible casework on where the 7 diameter circles could go and arrange the rest of the circles from that. There is most certaintly a better way, but this way took the least effort for me at least. Here is a picture of the correct answer down below.

Problem 2

Now, I actually didn’t do this problem except till the night before. That’s where my peak productivity for this contest is apparently. So there was the thing, that I just read the problem completely wrong. I did not see that the areas of the black and white regions had to be equal.

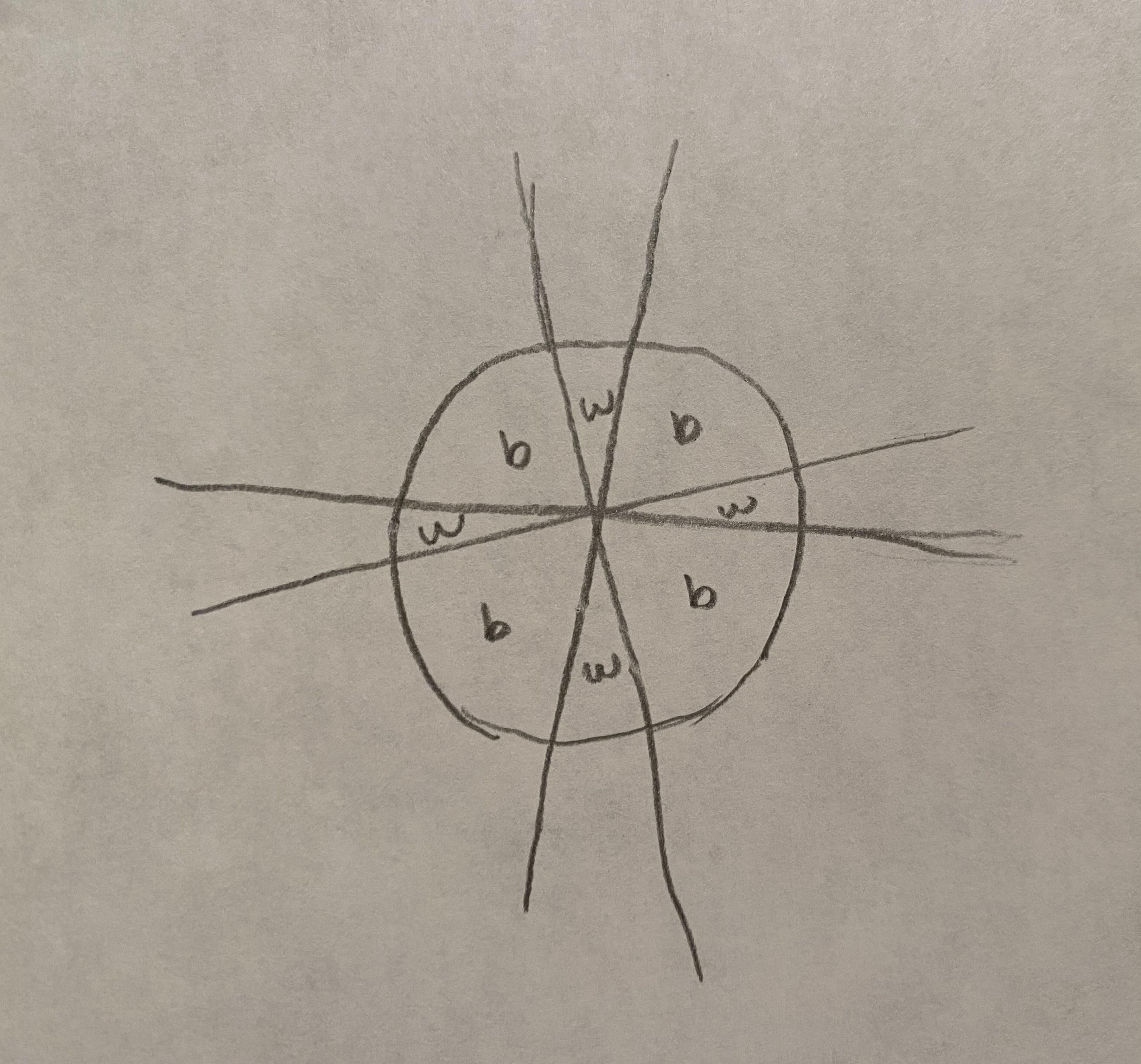

Instead, I thought it was purely the number of regions. So I was very confused because I kept thinking “literally everything works, how is this a problem.” But yes, after reading it again three hours before submission, I was so upset. I still attempted it though! It made it easier for me to visualize this problem with a tennis ball and some rubber bands because I do not have the best spatial awareness.

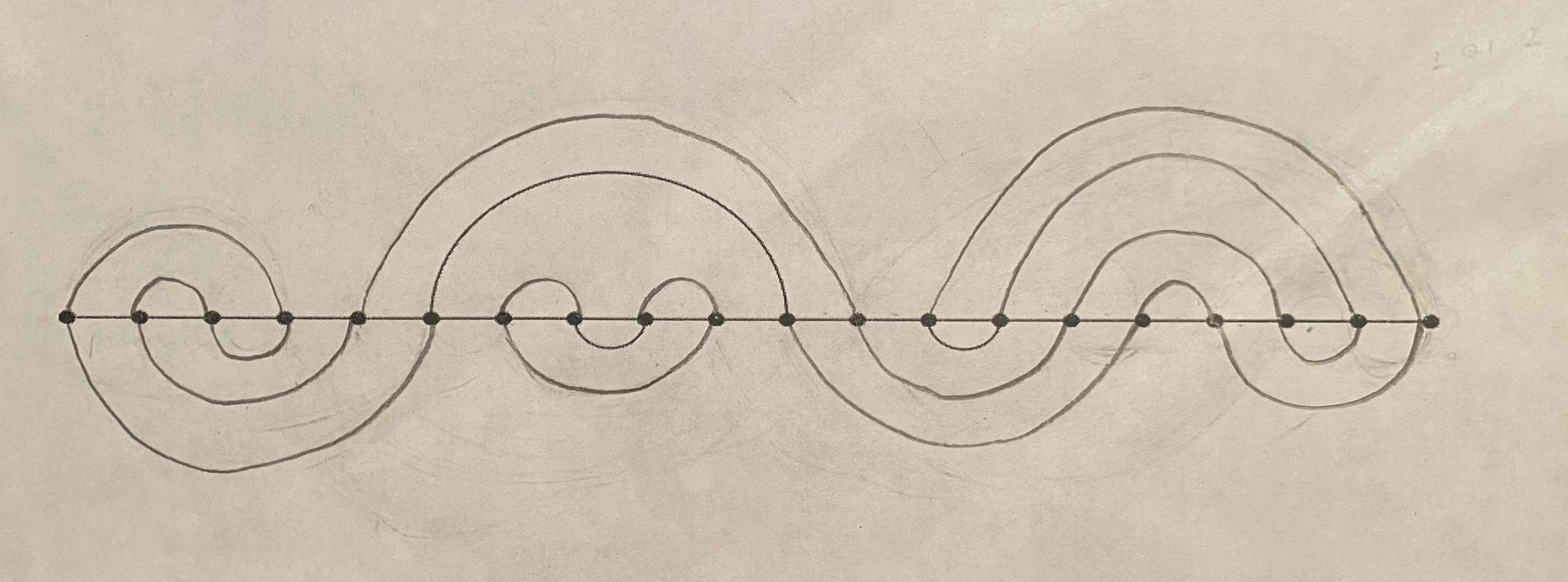

So the easiest way to do this is to just draw out pictures for the n = 1,2,3 and 4 cases. It’s easy to see that n = 1 works since it just divides the circle in half. n = 2 was easy to disprove since you can just make the angle between two arcs really really tiny so the areas would be unequal.

As we can see above, for the n = 4 cases, I could see immediately that you can just configure any even n like that. I used that fact to prove that odd n work.

I started off with an even configuration and then see what would happen when you added another great circle. Well, first the colors on one half would invert and then you get two more new regions.

Problem 3

So this problem seems intimidating. The way that I did this problem was certaintly not the best. I’ll discuss the better way to approach this problem.

So we notice that the numbers described are awfully specific, which calls for a generalization! The 1000 seems to specific. I noticed this after playing around with wolfram alpha for a bit, which I suggest you do for these types of problems. Gaining intuition. So we can generalize the $2^{1000}$ to $2^n$ and use induction which is straightforward from there.

A tidbit that is interesting to notice that if you take the expression mod $2^{12}$ let’s say, then everything from $2^{13}$ and above cancels. That is how I centered my proof, and proceeded to assume by contradiction that there is some point $2^k$ at where you can’t have 1 or 2 for that term and disprove that. It was a very long and ugly proof but it got the job done.

Problem 4

Now this problem was a woozy. For this, I used actual cards and played the game with my brother to get a sense of what was happening. After playing for a while, you can see that Grogg and Winnie will just start alternating cards at one point.

Let’s take the n = 4 scenario. So we have the cards 1, 2, 3 and 4. We know that Grogg goes first and let’s just say`that he puts down the 3 first in one pile. So Winnie’s logical move would be to put 4 next in that same pile. We see that if Grogg puts down a 3 or 4, that’s bad. To minimize this his optimal move could be to put down 1 first. Then we would have Winnie put the 4 with the 1. This leaves Grogg to put 3 in the other pile, and Winnie puts 2 with the 1 and 4. This makes a final sum of 5.

In this similar fashion, I made the grand mistake of thinking that the optimal move for Grogg was to put down a 1 first and then Winnie puts down a 50, Grogg puts a 49, Winnie puts a 48 and so on. Although! I didn’t account for the fact that no matter what Winnie will want to make sure that the 50 and 49 are in the same pile. So it’s actually Grogg’s best move to put 50 down first which is something that I totally overlooked.

From when Grogg puts down the 50, then Winnie and Grogg start to “alternate”. So I was almost there but not quite.

Problem 5

This problem was my favorite by far! It was the first one I started working on even before the puzzle.

I liked this mostly because of how straightforward it is and how simple the proofs are. Not to say that they were easy to think of, but they were really clean.

My solution here for 5b is different than the one presented in the AOPS math jam, although I think it’s pretty good. For 5a it’s quite simple to see the polynomial $n^2 + 2n + 37$ after some tinkering around with $p^2 + (p+6)^2 + n^2 + 1$ by expanding it out. Although how to prove it’s irreducible? It’s obvious it is, but that itself is not a proof. A way of suggestion would be that the discriminant is negative or by using Einstein’s Irreducibility Criterion. I did the second one just for fun.

For 5b, I first saw that 27 was a pseudo sixish number first by just trial and error. I used wolfram alpha to make the calculations less painful and to just see straight up. This is what led me to believe it was the only pseudo sixish number because after going up to 100 or something I didn’t reach any others.

Proof Sketch: So I wrote out the divisors of n as $(d_1)(d_2)(d_3)…(d_n)$ and then I wrote out the sum of squares of the divisors as $(d_1)^2 + (d_2)^2 … + (d_k)^2$. I wrote n as a product of some two divisors $i$ and $j$ such $n = (d_i)(d_j)$ and so $2(d_i)(d_j) + 36 = (d_1)^2 + (d_2)^2 … + (d_k)^2$. So we can write $36 = (d_i - d_j)^2 + (S_{rest})$ where $S_{rest}$ is the sum of the rest of the divisors besides $d_i$ and $d_j$, now we’ve reduced the problem to just finding the sum of squares that add up to 36.

There. The problem is simple with some casework and then you’ll find that 27 is the only pseudo sixish number.

Final Thoughts

I believe that this round was definetely easier than others, but hey, I’m not complaining. Although just looking at the Round 2 problems, I am seeing quite the challenge. There seems to be another game theory problem and the fact that they have no originality with names. They used Grogg again in the second round. Though, he was my favorite character in the Beast Academy books.