A USAMTS Year 34 Round 2 Review

What’s USAMTS?

USAMTS is a free, high school oriented, proof based contest that is funded by NSA. The contest consists of three rounds, each with 5 problems and worth 5 points. The contest is fully remote and is a month long since the problems are hard enough to not get immediately. The contest is a great way to think about problems constantly and sharpen your math skills.

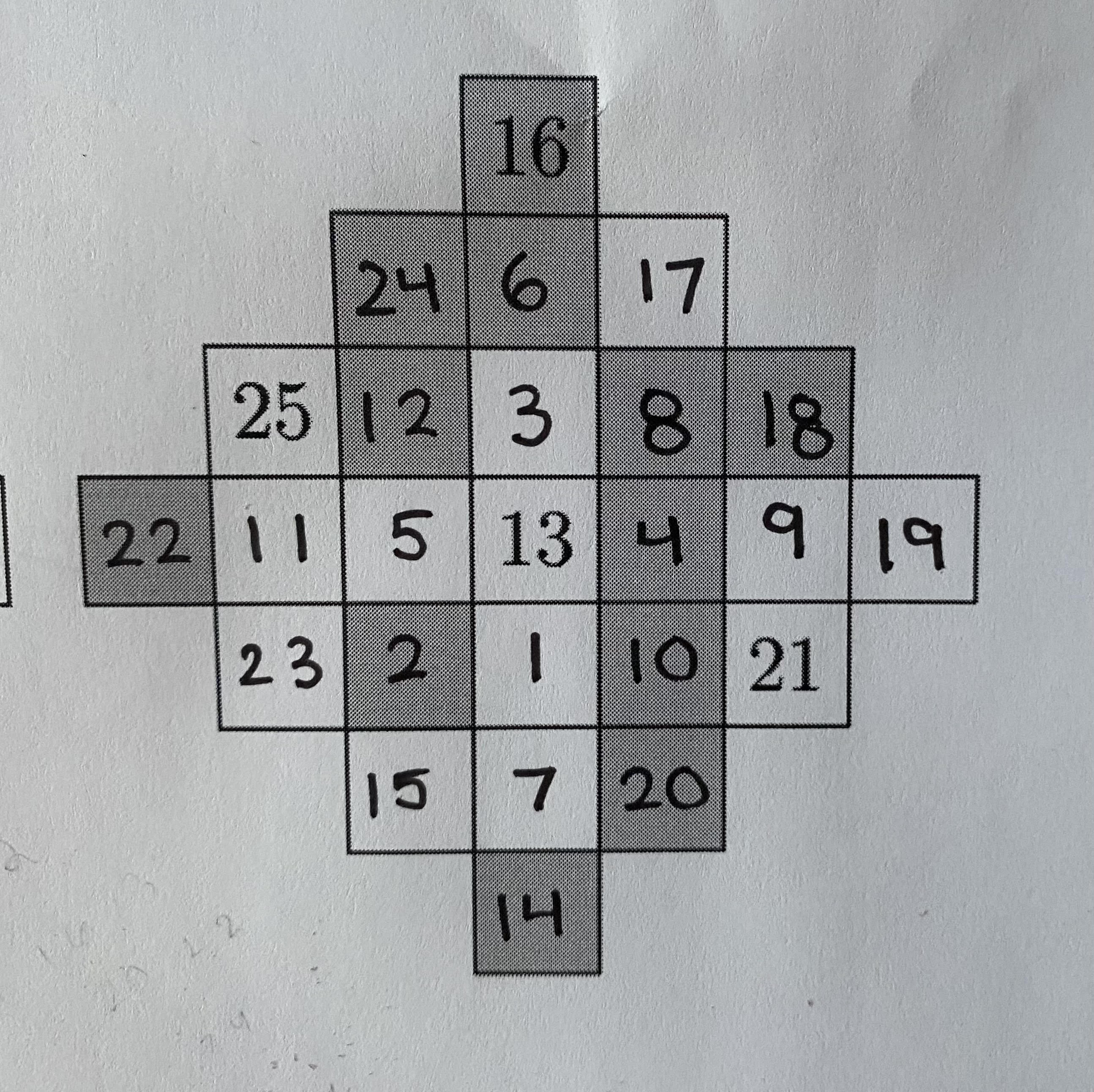

Problem 1

I don’t know if this is just me but I felt like this puzzle was harder than other years. I spent quite a lot of time on it. In fact, for this problem the only clue that I had for a while was that 5, 3, and 1 had to go into the center white squares. To be honest, it was hard to see how to not solve this without coding. Although, I eventually got the answer.

A starting strategy that I had was to list what numbers could go in each box. This strategy didn’t work if the squares were “lone” meaning that there are no given squares around it so you kinda just had to leave those alone. Following the diagram below,

we notice that the square with 4 on it could only be 2, 4, or 6. The square with 9 on it could only be 7 or 9 since there is the 21 below it. I approached the problem like this and made a giant table of the possiblites that could be made with each square. Basically after playing around with it, there was a point I realized that some odd numbers like 7, 9, and 11 pair up with 19, 15, and 23 in some pairing order. So that’s how I based my casework. Once you placed those three pairs all the other numbers usually fell into place to arrive at the solution.

Problem 2

This problem was actually really easy, although I read the problem wrong. Just applying the basic principles of expected value gets you the answer. The only values we have are 0, 1, and 2 since Grogg flips a coin only once a day. I started doing the case where he flipped it infinite times a day.

Let’s call probablity where he fufills the second condition of getting a cookie, T.

The expected value of the value 0 is 0. The expected value of 1 is $p$ and the expected value of 2 is $pT$. So we essentially want to find $p + pT = 1$.

Now we need to find T. So we know that T is $n * p^{n-1} * (1-p)$. Now you should get an equation which you can factor. This would be $(p - 1)(1 - n*p^n)$, and so you get $p = \frac{1}{\sqrt[n]{n}}$.

It’s a nice algebra trick. Just don’t be like me and actually read the problem. I do think an interesting extension would be if he flipped it infinite times a day which would turn into summing infinite amounts of infinite series; actually, I don’t know if that is possible but cool to think about.

Problem 3

This problem was interesting and honestly pretty straightforward. I first experimented with small values of n. We know that with n = 3 we cannot do anything, since we will always be stuck in a cycle of just having two numbers the same and then an outlier.

Although, notice that with n = 4 we can come up with a winning strategy. So let’s say we have the numbers a, b, c, and d. Then we can create the sequence, $\frac{a+b}{2}, \frac{a+b}{2}, \frac{c+d}{2}, \frac{c+d}{2}$. Then we can average out $\frac{c+d}{2}$ and $\frac{a+b}{2}$ to get some average “v”. Then our sequence becomes v, v, v, and v. This gave me the incorrect assumption that it was actually only the even numbers that worked.

So my proof was an incorrect proof of how the odd numbers could never work out. I used proof by contradiction but I think I messed up when I said that you can split the sequence into two parts and how one of those parts will have an extra number in it. That’s some pretty flawed reasoning now that I look at it since it doesn’t take into account all of the cases. Can you tell I submitted this problem set at 9:58?

Anyway the correct answer was that any composite $n$ works, so techinically I was kinda correct i just had a subset of the answer.

This makes a lot more sense actually. So let’s say we have some composite n, then it has some postive divisor that isn’t 1 or itself. If $d_1 * d_2 = n$, where $d_1, d_2$ are not 1 or n then we have can $d_2$ groups of $d_1$ numbers each. Let’s average the $d_1$ numbers in each groups so we achieve $d_2$ different numbers with $d_1$ of the same number in each.

Now, let’s say that we take a number from each of the $d_2$ groups to get some average. We can repeat this $d_1$ times to get a final average. I don’t know why I didn’t think of this since it’s a simple generalization from even numbers.

Problem 4

This problem was quite fun. Actually I think I got partial credit on this one since I messed up one of the cases. I started off by graphing the cases for small $k$ like 3, 4, or 5. It was pretty easy to see the pattern with even k.

You could just alternate between two rows that had two colors each in it to give $c_k = 4$ for even k. I messed up with the odd k, I guess this case was more complicated though. I also only considered one quadrant of a $k \times k$ coordinate system. So I would only consider the box: 2k x 2k squared centered at (0,0) since from further on it’ll repeat.

Then I tested out the odd ones, which gave two different answers. With $k = 3$, I first got 8 colors since I tried my strategy with even k but then that didn’t quite work out so I added extra colors. Guess I missed a color somewhere since the answer was 9 for k = 3. Pretty sad about that actually because I spent a good 1 hour carefully graphing this thing.

Although for when $k > 3$, luckily I got that case and noticed that there only needed to be 5 colors. With this problem it was more so experimenting and guessing. The proof came naturally afterwards with direct proofs.

Problem 5

I don’t know why but the problem 5’s have been really good this year. This was also a problem that I knew I could solve pretty easily. There is actually enough information given to coordinate bash this problem so that’s the approach that I took and then I just named Point E some point $(e,0)$. Although, the solution given on the USAMTS webiste using Cyclic quads is a lot more cooler.

We can utilize the fact that the line connecting the distance between the circumcenters is perpendicular to the radical axis. Since the radical axis is EF which gives us a really nice way to coord bash. All we need to do is find the circumcenters.

Just find the perpendicular bisectors of each side of the triangle and find where they intersect. I checked my work using a Wolfram Alpha Widget and then you can just repeat this process for each triangle. We recall the fact that if we have a line of slope $m$, then slope of a line perpendicular to that is $\frac{-1}{m}$.

You’ll end up with $y = \frac{s(x−e)}{1+3r−2e}$ as the equation. It’s simple to notice that we don’t want $e$ in our x and y coordinates so we have to get rid of “$e$” somehow. This can be done by noticing the $e$ in the numerator and the $2e$ in the denominator, so $x$ has to be $\frac{1+3r}{2}$ to cancel out that 2e in the bottom.

This means $(\frac{1+3r}{2}, \frac{s}{2})$ is our answer. I liked this problem! I did wish I saw the cyclic quadliateral approach though.

Final Thoughts

Overall, this round was pretty approachable. Good news, I got a 21 on the first round so let’s hope I get around the same for this round. But I made a lot more mistakes so we will see. Round 3 looks tough but there is winter break for a reason I guess.